Markets have continued to rise and fall on the basis of the prospects for the rollout of an effective covid vaccine. Recent news from Russia that their authorities had approved a vaccine was greeted by market enthusiasm and medical skepticism, since the treatment hasn’t been through complete safety and efficacy testing.

There are currently hundreds of vaccine candidates under investigation; a handful of these are already in advanced testing thanks to a relaxation of regulatory conditions and pledged government financial support. Still, investors should retain a little healthy skepticism. It is typically an arduous and expensive process to bring a vaccine to market. All of the vaccines in late-stage testing — the ones that are the best hopes of markets and health authorities — employ novel technologies that have never yet produced an effective vaccine in humans (including genetically engineered viral vectors and messenger RNA). Polls reveal high levels of public skepticism about the safety and efficacy of these new vaccines, even if they get official stamps of approval.

On balance, while it is almost certain that vaccines will be produced, we remain unconvinced that they will ultimately prove to be completely safe and effective — or that they will meet with sufficiently widespread public acceptance, whatever regulators may say.

The holy grail of this whole process is to reach “herd immunity.” When 60 to70% of the population is immune to the novel coronavirus, according to epidemiologists, covid will burn itself out, not having enough available hosts to continue its spread. If that herd immunity can be achieved with a vaccine, the thinking goes, we’ll be able to get back to normal life much more quickly and with much less loss of life; while if vaccines disappoint, trouble will lie ahead for markets and economies.

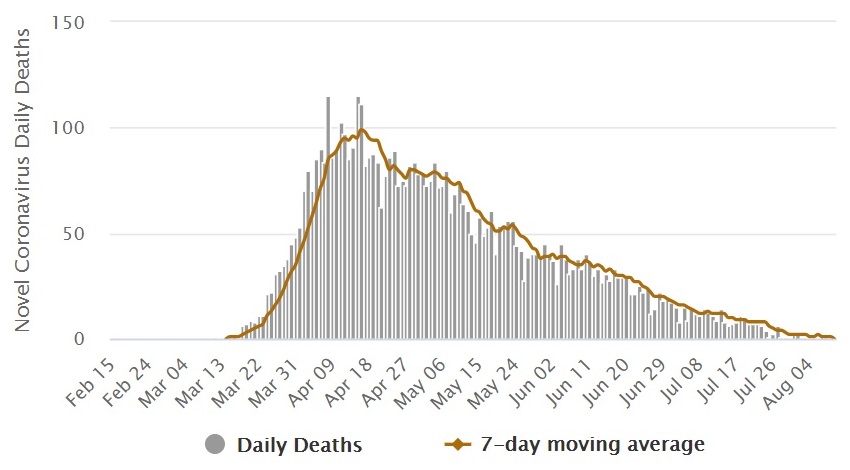

However, some scientists and physicians see data that suggest herd immunity may be closer than we think, even without a vaccine. Consider the way the pandemic has unfolded in Sweden:

Daily New Covid Deaths in Sweden

Source: Worldometer

Sweden’s covid strategy was very different from that of most other developed countries: no lockdown, no closures, no mandatory masks, no enforced social distancing. Measures were voluntary and targeted at protecting the most vulnerable populations (marred by the same failure to concentrate on long-term care facilities that dogged New York’s Governor Cuomo). The pandemic has now ended in Sweden, with daily deaths falling to the single digits. Health authorities maintained the controversial position that mandatory measures would be not just ineffective, but might even be counterproductive — and on the face of it, they were right. Sweden has achieved an outcome similar to that of regions such as Lombardy and New York (where the pandemic has now also almost run its course) but without employing the draconian social control measures that some governments have, with as-yet incalculable effects on their economies, schools, children, public psychology, and social cohesion.

How can this be? Emerging data suggest that it could be because a significant level of immunity to covid already exists in the population, thanks to exposure to the common cold. (Remember that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes covid, is a coronavirus, in the same family as many of the viruses that cause the common cold.)

An article published in Nature on July 15 studied T-cell immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 among survivors of the SARS outbreak — another novel coronavirus that emerged in Asia in 2003. (Interested readers can find the study here.) Remarkably, the authors found immunity in control patients with no history of exposure to SARS or SARS-CoV-2: “We also detected SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells in individuals with no history of SARS, COVID-19 or contact with individuals who had SARS and/or COVID-19… Thus, infection with betacoronaviruses induces multi-specific and long-lasting T cell immunity against the structural N protein.”

Another paper, published in June in the medical journal Cell, found reactive T cells in 40 to 60% of unexposed individuals. The authors noted: “Importantly, we detected SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD4+ T cells in ∼40%–60% of unexposed individuals, suggesting cross-reactive T cell recognition between circulating ‘common cold’ coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2.” (Interested readers can find the study here.)

We note that this is highly reputable, peer-reviewed research published in premier academic journals of medical science — not politically motivated opinion mongering.

Widespread pre-existing T-cell immunity in the population would explain several otherwise anomalous characteristics of the pandemic. For example:

- why serious illness and mortality skews so heavily towards the older and the immunocompromised, since T cell function declines with age and poor health;

- why the pandemic has been worse in impoverished countries with poorer overall health conditions, since malnourishment also suppresses T-cell function;

- and why the pandemic seems to burn itself out once actual SARS-CoV-2 infection reaches a 10–20% prevalence in a population.

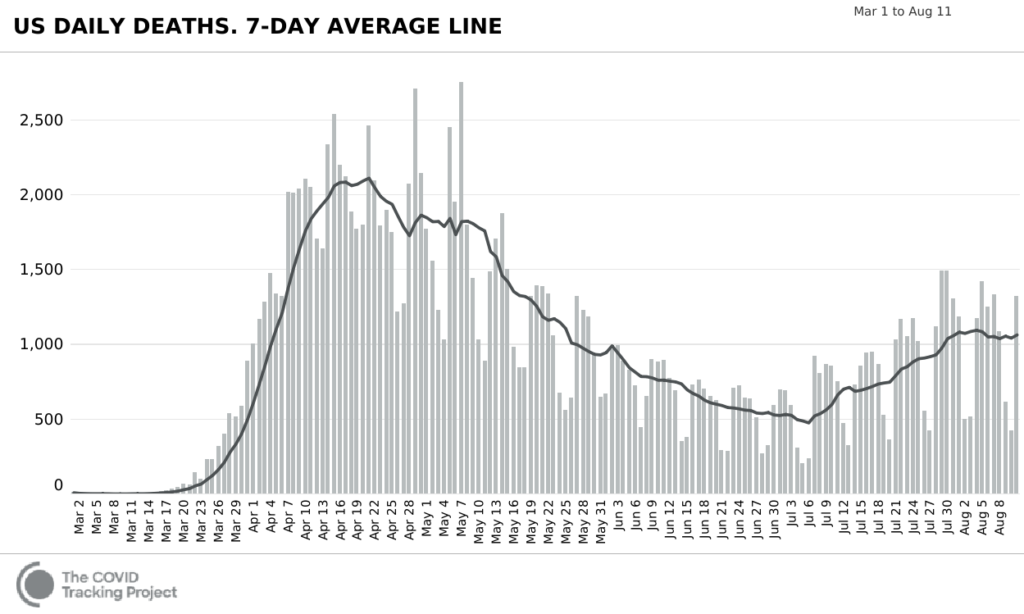

Added to the 40–60% of the population that has a pre-existing T-cell immune response from crossover immunity, that 10–20% may actually reach the “herd immunity” threshold needed to stop progression of the pandemic. We may be much closer to that threshold than previously thought — which may also explain why the rise in new cases in the U.S. is rolling over.

Source: COVID Tracking Project

Investment implications: If the above analysis is correct, the end of the pandemic may be closer than previously thought, whether or not there is a vaccine that meets with sufficient public approval and adoption. Under those conditions, the economic recovery could be more robust and rapid than the consensus expects. Coupled with historically unprecedented synchronized global fiscal and monetary easing, such a recovery would provide a powerful impetus to risk assets. In short, the data we review above should give investors a reason to think about “what might go right” rather than simply considering “what might go wrong.” The long-term consequences of this easing may well be detrimental, but that should not blind investors to the nearer-term opportunity, particularly in the event of politically driven market volatility. For the longer-term concerns, gold should remain a central element of investors’ strategic thinking.