Another month, another blistering inflation report; the consumer price index rose at a 7% annual rate in December. Of course, as our regular readers have heard us say often, the methodology used to calculate that rate has changed often over the decades — invariably in a way that understates the true inflation experienced by consumers, but useful to the bureaucrats and politicians for whom inflation is a costly bugbear. If CPI were calculated as it was in the 1980s, it would be at about 15%, according to ShadowStats.

Source: ShadowStats

ShadowStats is useful, but at Guild, we felt the need decades ago to construct an unadjusted index that would let us track more closely the real inflation experienced by consumers. Our in-house inflation gauge, the Guild Basic Needs Index (GBNI), is comprised of a basket of basic elements representing consumer expenditures on food, clothing, energy, and shelter. Of course, it is more volatile than the official CPI, but therefore also more sensitive to what is happening “on the ground” and what consumers are actually experiencing. The GBNI peaked just above the 30% mark back in October. We’re still awaiting final December data for some components, but it is still tracking in the high 20s.

Commodities and Inflation Defense

Inflation is here; the Fed missed the boat, having adopted its FAIT (“flexible average inflation targeting strategy”) at precisely the wrong moment — just in time to encourage it to dawdle while post-pandemic inflation pressures were building and visible to just about everyone. The reality of inflation has for some time had intelligent investors considering commodities as a solution to mitigate inflation risk.

Unfortunately, it’s not a simple matter to select a commodities allocation, even in the era of exchange-traded funds and notes. There is still the basic quandary of whether to get exposure to commodities themselves via futures, or to the stocks of commodity producers and other commodity-exposed companies, or to the country-level indexes of commodity-producing nations. (Spoiler: with a few fundamental and tactical exceptions, we prefer the second of those three options.)

Commodities are rendered even more complex in the current environment because of a number of converging global macro trends that are unfolding.

Gold and Digital Assets

According to the World Gold Council, globally, about 48,000 tons of gold are held by private investors in the form of bullion and ETFs (this excludes jewelry and industrial holdings). That’s about $2.8 trillion. At this writing, the market capitalization of bitcoin is about $830 billion. We regard bitcoin’s primary eventual use-case — leaving speculation aside — as being that of a “digital gold.” It is notable that global bitcoin holdings already stand at 30% of the total value of gold held primarily for its “store of value” characteristics. Clearly, bitcoin is providing significant competition to gold in this regard, and given the ease with which bitcoin can be bought, stored, and traded in the post-pandemic world of digital acceleration, we do not believe that its competition with gold is likely to be fundamentally blunted in the near future.

In the event of a significant bitcoin decline, which in our view is likely, we believe that there will be significant institutional buyers, and that it will rebound, as it has after all its historic crashes. While gold is not down for the count, it is certainly seeing its luster challenged by digital assets. (We exclude the considerable market caps of other digital currencies, such as ether, from this analysis, as these currencies and tokens serve a variety of other purposes besides value storage. This makes them very interesting items of speculation in their own right, but not specifically inflation defense tools.)

China, the Belt and Road Initiative, and New Trade Among Europe, the Middle East, and Asia

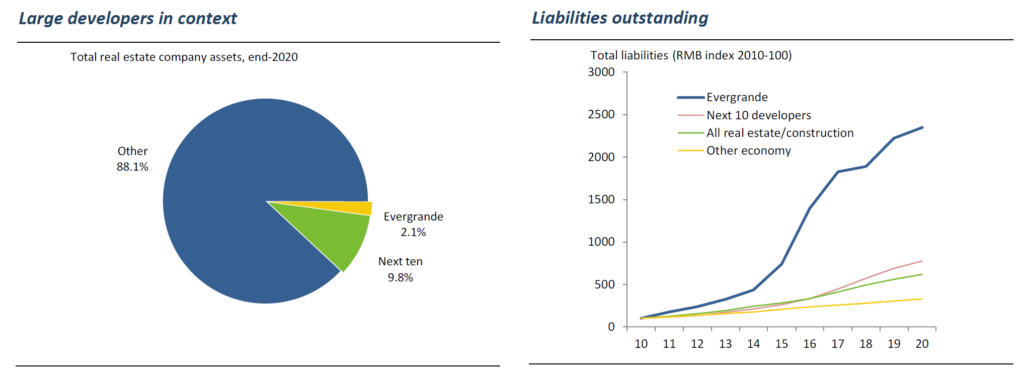

The last commodity supercycle was driven largely by Chinese economic growth in the 90s and aughts, which saw the largest and most rapid urbanization in history and consumed much of the world’s raw materials in the process. China still accounts for 55% of global metals demand, but the environment is very different now, both economically and geopolitically. China is a more mature and deceleraring economy now, and is facing potential headwinds from the unwind of large financial excesses that built up in the course of the last few decades of growth. We do not believe these will be catastrophic. It is being partially replaced by new infrastructure projects in Europe, the mideast, and central and southeast Asia. In addition, the risk posed by China Evergrande is really quite small, a relatively minor outlier seen against the backdrop of the larger China property sector.

Source: Emerging Advisors Group

But the larger process of deleveraging, even if it is unlikely to be catastrophic, will likely be a drag on the country’s commodity consumption.

The Energy Transition

A further large macro force at work in the world is the global transition — slow in some areas, faster in others — from carbon-based energy to renewables. That shift will require a huge input of materials related to electrification — copper, nickel, lithium and other battery minerals, and rare earths. This process itself will be inflation-generating; European Central Bank executive board member Isabel Schnabel last weekend became the first world central bank officer to acknowledge publicly the inflationary influence of decarbonization.

On the carbon front, however (“black” energy rather than “green”?) we note potential as well. The push and pull here is that although carbon energy producers will be under a cloud of public and regulatory disapproval, the demand for their products will be robust for decades, as Europe’s recent decarbonization stumbles have shown. They will thus likely continue to provide income streams for investors even as the appreciation of their stocks is challenged in the longer term. The U.S. shale industry’s growth, though, means that unlike in the last big run for energy, the world knows there are large reserves whose taps can quickly be turned on — and that is a headwind for rising oil prices.

We note also that rising hydrocarbon prices will also benefit some agricultural chemical providers, as noted below.

Advocates for social causes also have extractive industries in their sights, and Chile’s recent election of a resource-nationalist leftist demonstrates some of the risks that accompany developing-world commodity production — even in places long thought to be securely in the free-market camp.

The energy transition theme suggests areas of particular interest and particular caution to us in seeking commodity exposure.

Food

Since hydrocarbons are a big cost input for agriculture — both to create fertilizer and to power equipment — food prices are also rising in response. This is an area where investors can easily fall afoul of volatility, as extreme weather events can swamp other influences in the short run. In general, we view these “softs” as tactical opportunities rather than longer-term themes, and currently do not find any attractive.

Investment implications: Although commodities are a long-term response to inflation with a long history of defensive use by investors, most commodities in the current environment are challenged by a variety of crosscurrents. We are fundamentally long-term positive on gold and believe it may appreciate this year, even as some of its appreciation potential continues to flow to bitcoin and other store-of-value digital assets. We are most interested long-term in tech-related commodities relevant to the buildout of global green infrastructure, particularly battery technologies. Some hydrocarbon energy companies will still have good cash flow that they distribute to investors through dividends and buybacks, but their price appreciation will be limited.