With the S&P 500 bouncing off very long support at the 200-week moving average, the stage may be set for the bear market to get a breather. Inflation remains a clear problem, but as we have been telling you for some time, inflation will eventually begin to settle back from its highs. Many inflation data are highly backward-looking. We continue to anticipate that inflation will not persist at the highly elevated levels we’ve recently seen, but think that it will reset significantly higher than in the disinflationary decades that followed the accession of China to the World Trade Organization and the Dot Com crash.

Fiscal and monetary policies around the world are in conflict. Inflation was sparked by extreme fiscal profligacy in response to the covid crisis, and that is far from reined in; even as central banks are tightening, governments are spending in response to new crises (viz., Europe). Government will win, we believe, and “independent” central banks will lose. Government will get what it wants, which is a moderate inflation significantly above that of recent decades, to gradually reduce extreme public and private sector indebtedness.

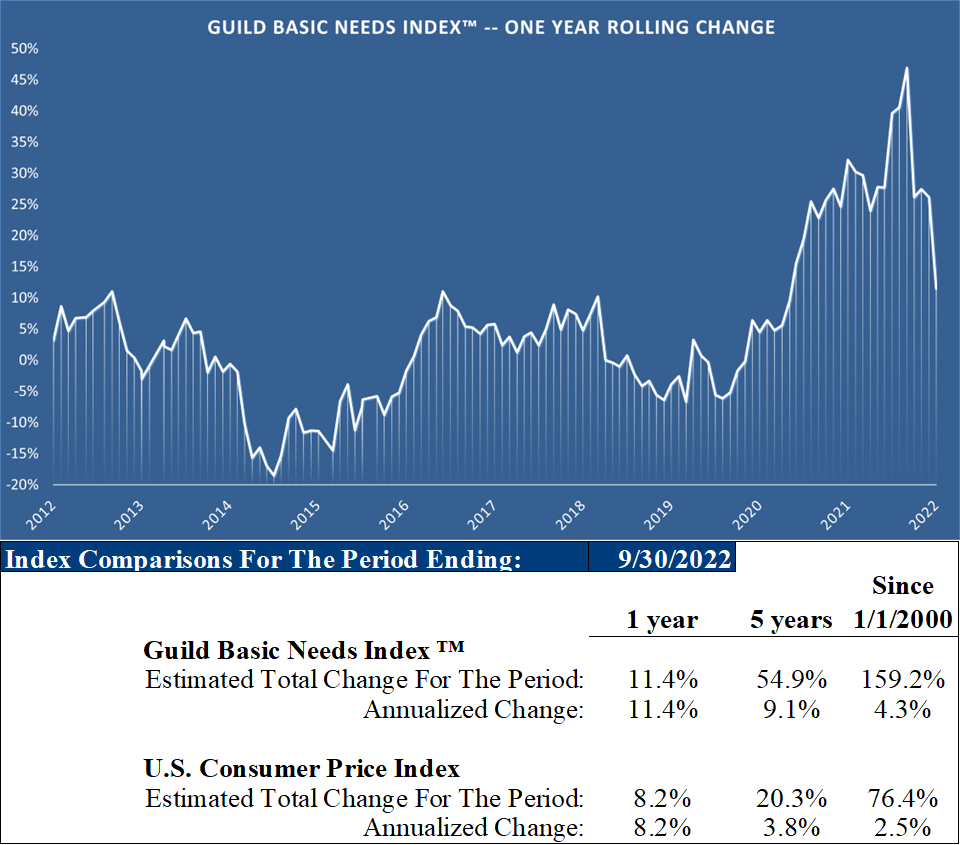

The September data for the Guild Basic Needs Index, our in-house real-world inflation measure, show inflation continuing to cool from its summer peak.

We see inflation running at 4–6% in the long run, driven by taxes, regulation, and ongoing chronic supply chain issues and shifts.

The Big-Picture Cycle

The fundamental reason is one that we have often pointed out in our letters since we identified a sea change in inflation back at the beginning of 2021. The big picture is one of long policy cycles.

We started such a cycle in the early 1980s, with the arrival of Reagan, Thatcher, and an era of deregulation. That led to a big improvement in productivity growth, particularly as a new, capital-friendly tax regime encouraged the development of new industries (such as the internet) and allocated capital more effectively than during the stagflationary, more government-directed era that preceded it. But nothing good lasts forever — and this cycle also ended up creating its own excesses thanks to unrestrained financial engineering and speculation, abetted by long-lasting ultra-loose monetary policies. Thus we experienced the Great Financial Crisis and the decade of quantitative easing that followed. This long period from the 1980s to 2020 was characterized by low inflation and declining interest rates, finally settling in near zero (whereas in Europe, absurdity became the norm, and rates stayed below zero for years).

A Blast From the Past

Now, in the aftermath of covid, we are entering a new cycle. This new cycle is shaping up to be similar to the one that preceded the Reagan revolution, running from the end of the Great Depression, through the Second World War, and into the post-war boom and eventual slump into the stagflation of the 70s. This was a much less laissez-faire era, when government policy, rather than an independent central bank, ran the show, through fiscal and regulatory means. It was put into place essentially to engineer a slow and controlled debt deflation from the excessive debt levels accrued as a result of the Second World War and the reconstruction of Europe.

In hindsight, it worked out pretty well for quite awhile. The post-war debt pile was inflated away over a period of several decades, and during much of that time, the U.S. enjoyed a strong economy. In the late 60s and the 70s, the rosy picture ended, as decades of higher regulation took their toll, and resource crises and the pressures of excessive domestic and military spending pushed the U.S. into a stagflationary period — high inflation and high unemployment. Eventually, voters around the world “revolted,” the cycle turned, and while the U.S. and UK embraced more free-market policies under Reagan and Thatcher, countries around the world started to abandon communism and central planning.

Now we have another debt pile to inflate away, and thus we may be entering another era where independent central banks are sidelined, and governments exert more direct influence on the creation of broad money. We saw the beginnings of this during the pandemic, with government guarantees of private sector loans; Europe is now doing the same thing in response to the energy crisis brought to a head by the Russian war in Ukraine. Governments that can guarantee private-sector credit can have a profound influence over what sectors and industries are favored as they pursue their goal of deleveraging the economy by steady, moderate inflation (if they are skillful and all goes according to plan).

What’s interesting to note is that in the beginning of each of these cycles, the economy and the markets can actually perform very well, until excesses, distortions, malinvestments, and other problems crop up. The government-intervention cycle can begin with a burst of capital expenditure, and that may be something we’re about to start experiencing. The geopolitical troubles with China and Russia that are cancelling much of the globalist project will result in a lot of reshoring and “friendshoring” — which will all require extensive capital expenditure on new and improved plant and equipment as the world bifurcates into more suspicious, if not outright hostile, camps. Apple’s decision to build iPhones for the Chinese market with Chinese-sourced chips, and iPhones for other global markets with chips sourced elsewhere, is an example — as are big semiconductor fabrication plant expansions in the U.S. Some are the result of the private sector responding to the changing environment, and some are the result of government political folly.

The aggressive expansion of green energy and infrastructure looks like an example of the latter — and this illustrates where eventually, much of the capex that is directed by government policy is going to prove to be unfortunate and inefficient malivestment — a sub-optimal deployment of human effort and wealth and ingenuity. Germany recently went hat-in-hand to Canada to ask for accelerated construction of terminals to export liquefied Canadian natural gas to Germany. Canada demurred, noting that they could not see “economic benefit” — and then the countries inked a preliminary deal to export hydrogen from Canada to Germany. We are generalists who try to be informed and thoughtful, and we do not claim to be energy experts — but even we could see such a scheme to be an utterly pointless boondoggle, since hydrogen is an energy storage technology, not an energy generation technology. Doubtless it would be a highly profitable boondoggle for whoever is building the infrastructure that receives the anointing of the government. In the U.S., the recent releases from the strategic petroleum reserve [SPR], which have taken it down to a 20-day supply, are to us a similar lamentably political use of what should be a neutral economic and geopolitical safeguard. The U.S. citizenry would better be served in our opinion if these “strategic” reserves were tapped in real emergencies, not political emergencies.

Germany’s real problem is that extreme ideology has led it to shutter its richest energy sources in favor of energy sources which require far more resource inputs to produce a unit of far more uncertain and intermittent electricity. The vast expansion of so-called decarbonized energy, requiring almost unimaginable investments in basic and advanced materials, was rendered possible over the last decade and a half precisely by cheap fossil fuels and cheap capital thanks to zero interest rate policies. Germany is already reaping the bitter harvest as it becomes apparent that more expensive fossil fuels and more expensive financial capital are revealing the utter inadequacy of the utopian energy system they have tried to build. But the rest of the world has a long way to go before it will reach that point, and over time, the fortunes of green energy will ebb and flow. One clear beneficiary of the whole process is apparent to us: nuclear, which is the sole universally available carbon-free energy source capable of powering the civilization to which we’ve become accustomed. Without nuclear, the carbon-emission-free energy future looks like a nightmare of deindustrialization. We believe the countries that have rejected nuclear will re-embrace it, and we are bullish long-term on uranium and on small module reactor technology.

But that realization may not really sink in for quite some time, and the capex boom in decarbonization is going to continue as long as governments push it — that is, as long as electorates demand it, or can be manipulated into demanding it. We suspect that many among the electorate will like what they see in the beginning of the government-directed cycle, because all that capex will produce various economic booms of various durations. The reshoring and friendshoring capex will provide economic activity, and the long, slow grind of inflation will have the “positive” effect of reducing real debt burdens. The various beneficiaries of these policies will reward their benefactors at the ballot box. The problems arise as this cycle advances. It eventually requires more and more intervention from government in one form or another of financial repression. The freewheeling epoch of financialization created by deregulation that began in the Reagan era, ripened to extremes in the Great Financial Crisis, and is being supplanted by a very different, more government policy-centric regime.

Digital Currencies Were Born of this Shift

Decentralized digital money was for some the answer to government encroachment (and growing corporate power). While a great idea and innovation, it became too big. We believe that the real result of digital currencies will be increased encroachment and more ways for government to control. The introduction of government digital currencies is imminent, and we expect severe restrictions, or in some cases outright attempts to ban private-sector cryptos. The government will not be able to eradicate crypto, but rest assured, they will be able to marginalize it and choke off its connections with the formal financial sector. That will be enough to channel the desire for digital currencies into an acceptance of government-backed digital currencies — and these, eventually, will offer governments some of the most robust and disturbing tools for financial control and financial repression that any governments have ever had. Bitcoin is still unique, and should retain some utility in this environment as a mathematically backed store of value, even if regulation prevents it from appreciating as much as it might in a genuine free-market context. Bitcoin will likely be viewed as a useful diversification, but the HODLers and maximalists may be disappointed. The truth is that at this part of the cycle, too many in the electorates around the world are looking to their governments (and not to themselves) for solutions.

Meanwhile, Traditional Currency Markets (Outside the U.S. dollar) Are In Disarray

The strong dollar has started to demonstrate its ability to cause fissures in markets. Sovereign bond markets, corporate debt markets, and commodity markets would much prefer it if the rush into the dollar abated. As it remains the largest world reserve currency, who can blame global allocators for hiding in U.S. dollars and earning the extra income the Fed rates are providing? The dollar is giving gold a hard time, and until the dollar stops going up, it will continue to have a hard time. However, in the long run, it is difficult to see that gold will not benefit in the financial environment that is emerging.

All of this is to say — do not expect a rapid return to the economic reality that is the only one familiar to those who came of age in the 1980s and later. We are headed into something different — something where the old term “political economy” is going to take on a new relevance. It will certainly not be some kind of recognizably Marxist command economy — but it will be one where political factors outweigh purely economic factors in decision-making. And again we stress: this can be an environment in which economies and markets perform well for quite some time before the distortions become overbearing and there needs to be a political paroxysm to clean the slate and start over.

Markets Looking for New Leadership

There is a reason for optimism. In the nearer term, as we noted above, the market’s bounceoff very long-term support suggests that a bear market rally can continue — even though we still expect that a deeper earnings trough lies ahead if we land in a full-blown recession. Technical analysts suggest that a bear market rally could be significant from here, posing the question of what the market will settle on as it looks for leadership. Strong results from some big banks suggest that until a deeper recession were to come into view, financials are perhaps the most likely candidates for that leadership. Energy — particularly legacy energy — definitely has the results, but can’t pass ideological muster for leadership of the wider market. Tech and healthcare are also possibilities. There will be a lot to listen to in a busy and consequential earnings season that is just now getting underway, and we’ll be bringing you our observations.

Thanks for listening; we welcome your calls and questions.