Does the collapse of the U.S.-backed Afghan government matter?

It certainly matters to many Afghani individuals who hitched themselves to the American star, and seem to have been unceremoniously abandoned in the chaotic rout that passed for an American withdrawal. It matters to the population of young urban Afghanis who developed a taste for some western political and cultural amenities over the past two decades. It will likely matter to a host of shadowy opportunists from Iran, China, Pakistan, and elsewhere who stand to benefit from the procurement of Afghan mineral wealth, and to U.S. military contractors who will see the end of what was certainly a gravy train for the ages. But beyond the local tragedies and disruptions, there are deeper implications — and these deeper implications could ultimately be quite significant to investors.

Primarily, this event is a message sent, unintentionally it seems, from the United States to the world — and it is not a message that will have a beneficial effect for U.S. diplomacy and U.S. economic hegemony.

China Gets the Message

On Tuesday, a Chinese government organ, the Global Times, published an op-ed piece with a pointed message for the government of Taiwan:

“In the past two decades, the Kabul government cost over 2,000 U.S. soldiers, $2 trillion, and the majesty of the U.S. against the ‘bandits.’ But how many lives of U.S. troops and how many dollars would the U.S. sacrifice for the island of Taiwan? After all, the U.S. acknowledges that ‘there is but one China and that Taiwan is part of China.’ Will the U.S. get more moral support from within and from the West if it fights for the secession of Taiwan than it did during the Afghan War?

“The DPP [Democratic Progressive Party, the current ruling party in Taiwan] authorities need to keep a sober head, and the secessionist forces should reserve the ability to wake up from their dreams. From what happened in Afghanistan, they should perceive that once a war breaks out in the Straits, the island’s defense will collapse in hours and the U.S. military won’t come to help. As a result, the DPP authorities will quickly surrender, while some high-level officials may flee by plane.

“The best choice for the DPP authorities is to avoid pushing the situation to that position. They need to change their course of bonding themselves to the anti-Chinese mainland chariot of the U.S. They should keep cross-Straits peace with political means, rather than acting as strategic pawns of the U.S. and bear the bitter fruits of a war.”

That is, of course, the voice of Chinese threat and propaganda, and we should expect nothing different. Unfortunately, the ignominious events of the past week lend just enough credence to such threats that around the world, the confidence that allies have in the United States as a trustworthy and reliable geopolitical and economic partner may just have gotten incrementally weaker. Rest assured, China is far from the only adversary of the U.S. that has taken note of what the fall of Afghanistan represents.

The Anniversary of the Death of Bretton Woods

Why this matters can perhaps be seen in the light of another momentous anniversary that just passed. Fifty years ago this past Sunday, Richard Nixon closed the gold window, ended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold, brought an end to the post-war Bretton Woods currency détente, and brought us into the modern era of global free-floating fiat currencies. (The cultural revolution swirling around him as he made that decision has direct linear descendants in the progressive and neo-Marxist orthodoxies now vying for hegemony in elite U.S. institutions, but that is a tale for another time.)

The U.S. ultimately survived to thrive after the final demise of the gold standard for a simple reason: while gold retained utility as a form of wealth preservation for individuals, and as an element of holdings for central banks, the U.S. dollar now took gold’s role as the sun around which all the currencies orbit. It is important to recognize that the U.S. dollar is itself a product for which there is global demand. In a very real sense, the U.S. exports dollars and imports goods and services in exchange. This foreign demand for dollars is what has allowed the U.S. to run large trade deficits for many decades.

It is also important to recognize that the production of U.S. dollars in such a way that they remain in high demand is far from a trivial enterprise. In fact, the reason that demand has remained so high for dollars — the reason that dollars remain 60% of global central bank reserves — is that they are a unique commodity.

The “machinery” that produces U.S. dollars with the characteristics that global holders demand is the entire U.S. political economy. It is:

- A dependable system of property rights;

- The rule of law, which is largely predictable and reliable, as opposed to the rule of officials’ whims, which is neither predictable nor reliable, and eventually turns to theft and plunder in both brazen and subtle forms;

- Liberal democratic governance;

- A society in which ambition, aspiration, creativity, and initiative are celebrated and encouraged;

- A banking system operated with clarity, transparency, and sobriety;

- A stringent and strictly enforced accounting system in which misstated financial data are rare;

- A market for securities in which fraud is the rare exception and is prosecuted robustly; and

- A government that demonstrates great reserve in interfering with the daily lives and economic activities of its citizens.

Critically, it is also the capacity to project these values on a global stage. That means that however far or near other world governments may be themselves to the characteristics of the U.S.’ political economy, many of them at least publicly profess admiration for it (even if they profess dislike of whatever specific individuals comprise the U.S. government at any given moment). In a world where that system has competitors, would-be allies must know that they enjoy the moral, and if necessary, the military support of the U.S.

In brief, besides depending on the domestic economic, social, financial, and political reliability and dependability of the U.S., the foreign demand for dollars that ensures the dollar’s dominance also depends on the global prestige of the U.S., the credibility of its military strength and competence, and the reliability of its promises to allies.

The Afghan debacle is, unfortunately, a blow against all of those needed factors. We are not suggesting that this event will provoke an acute crisis for the dollar. We are simply noting that should the trend continue, it would eventually begin to undermine the dollar’s position. Of course, there is not presently a contender for the dollar’s spot on the top — nothing else even comes close. We do not see any likely candidate — certainly not the euro nor the yuan, and certainly not bitcoin, which lacks many vital characteristics of a reserve currency and has no pathway to achieve them. But that could change — and if the U.S. progresses further down this path, that would create pressure for such change.

Why then is the market taking all this with such apparent nonchalance? The answer, at this juncture, is simply “the flows.” Or, to use a popular acronym, “TINA” — there is no alternative.

Flows Have Been Extraordinary — and There’s More To Come

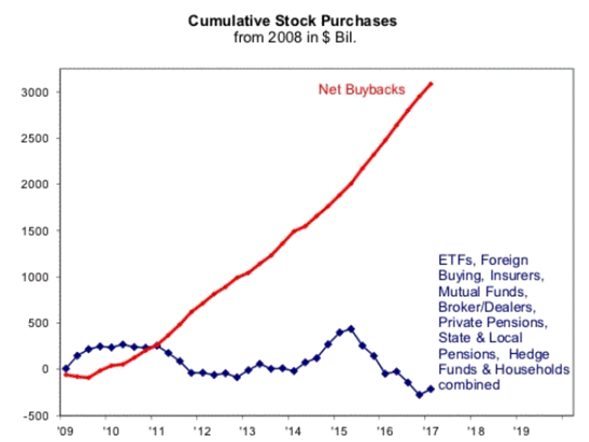

A few years ago, we posted the following extraordinary graph courtesy of then Canaccord Genuity analyst Brian Reynolds:

Source: Canaccord Genuity

What it showed was that on net, since the Great Financial Crisis, everyone in the U.S. had been sellers of equities except companies themselves. Buybacks were the name of the game, and the driving force behind the stock market’s rise. Of course, this was enabled by plentiful liquidity which gave corporates lots of cheap (free) cash to buy back their own stock.

Fast forward to today, and the situation is a bit different.

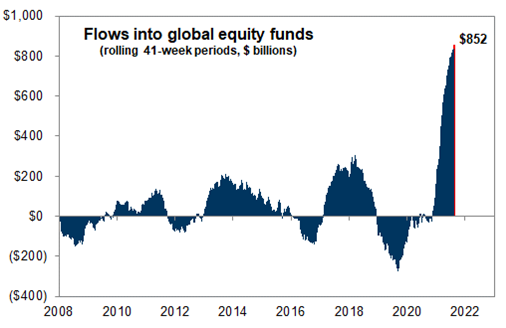

Goldman Sachs analyst Scott Rubner observed recently that global equity inflows in 2021 year-to-date have reached $605 billion. Inflows in the previous 25 years, from 1996 to 2020, were a cumulative $727 billion. (Note that these inflows are global, rather than the U.S.-only data that Brian Reynolds examined.)

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Research

On an annualized basis, then, global inflows to equities are on track for this year to exceed the past 25 years taken together — by 40%.

Year-to-date, inflows are coming at the rate of nearly $4 billion per day. This is ultimately a manifestation of the tidal wave of liquidity created by the global pandemic monetary and fiscal policy response. This is one reason why 2021 to date has seen nearly 50 new all-time highs — about one every four days.

Of course, some of this is also money sitting on the sidelines. So could it continue? Many trillions of dollars remain on the sidelines even now. Corporate balance sheets are flush with cash — up to $6.8 trillion in Q2 2021 from $4 trillion in Q1 2015 — that is ready to be deployed for something, the answer is yes, inflows could continue at this pace.

This, then, remains the overwhelming reality — liquidity being deployed to buy stocks at a pace that far exceeds anything seen in the past 25 years.

Allianz’ Chief Economic Advisor, Mohamed El-Erian, observed recently how deeply investors have been conditioned over the past two decades to buy every decline because there is no alternative to risk assets. He commented, “Given the deep conditioning of markets, and its positive reinforcement by financial rewards, a huge shock to market psychology — such as a serious policy mistake, a big market accident or a combination of both — would be needed to shake investors out of a mindset that has served them incredibly well so far.”

What happens during such a shock? Usually, a shock is preceded by a period of exuberance and high demand for stocks. Then the shock comes, and the sentiment of market participants flips — they no longer believe in companies or their prospects, believe they are overvalued, and precipitate waves of selling.

The pandemic has demonstrated that shocks can come from new and unexpected directions; in spite of decades of warnings from scientists, investors generally hadn’t really factored in the possibility of a medical black swan. We think greater volatility from unexpected quarters has become more likely moving forward. With that said, in most cases, given the determined support of policymakers which has helped produced the past months of astounding inflows to equities that we described above, most of these will be dips to buy.

Investment implications: Various trends are afoot that suggest future problems — problems for U.S. prestige and influence in the world, and problems for the dollar. But those problems are still far off. For now, the dominant reality is liquidity. Even though the pace of pandemic-driven liquidity growth has peaked and begun to decline, the amount of liquidity that is seeking to find a home in global stocks to us indicates that corrections occasioned by volatility are likely to be comparatively shallow and brief. The Afghan debacle is a stain on U.S. credibility — but for now, and likely for some time to come, this reality is far from the market’s mind. Buy the dips.