First we reviewed the great bull/bear debate; then we gave a rundown of global stocks; last week we described our view of the positioning of the high-level asset classes. Today we’ll round out the high-level tour with some analysis of global currencies.

Cash is of course one of the main asset classes; typically cash is thought to be “risk-free” in an even more direct sense than bonds. Bonds of course do have risk. The longer-duration they are, the more they fluctuate with interest rates. By holding shorter-term bonds from reliable issuers, investors can minimize that risk, even if they can’t eliminate it. Still, when it comes to short-term paper from entities like the Federal government of the United States, interest rate and default risks are sufficiently de minimis that investors shouldn’t spend a lot of time or energy worrying about them.

Cash, though, as the unit of account itself, doesn’t even have the duration risk of a bond. But still, as this year has illustrated, cash is not risk-free. The fundamental risk posed to cash as the unit of account is an element of the risk to all financial assets that are priced with that unit: the erosion of purchasing power. When inflation is underway — to simplify greatly, when the growth of supply of a currency is outstripping the growth of supply of the goods and services its holders want to buy — holders of cash experience that erosion painfully. It’s all the more painful when multiple asset classes are challenged at the same time — there seems to be nowhere to hide.

In essence, any fiat currency — that is, any currency which can’t be exchanged on demand for a determined quantity of some real-world commodity, typically gold — depends for its stability on the fiscal and monetary stability and responsibility of the entity that issues it. Most of the readers of this newsletter are residents of the United States, so the entity in question is the Federal government.

For decades, as Federal deficits and the Federal debt have ballooned, skeptics and dissidents have argued that the United States is abandoning its status as the most stable and reliable currency issuer in the world. As the world’s greatest industrial powerhouse for a century, with robust civil liberties, the rule of law, property rights, a functioning (if contentious) democratic system of governance, an open banking system, and global military pre-eminence, the U.S. produced a currency in universal demand, even after the end of the gold standard.

While the skeptics’ observations are largely correct, the conclusions they draw from them are not. Yes, the Federal government has fiscally sailed steadily further and further into debt, culminating most recently in the unrestrained orgy of spending to combat the effects of the pandemic lockdowns in 2020 and 2021. Yes, the monetary policy of the U.S. central bank has gone further and further into uncharted territory since launching massive multi-year programs of money printing (QE) in response to the 2008 Great Financial Crisis. However, their latest QE programs during the pandemic in 2020 and 2021 make the earlier episode pale in comparison.

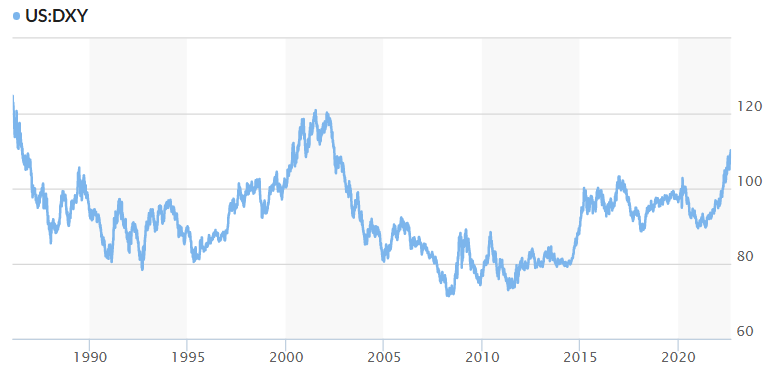

And yet, here in 2022, after that monetary and fiscal tide, the U.S. dollar still reigns supreme among its global peers. And here’s the rub: there is no “neutral currency.” There are only the real currencies issued by real governments. And while some of the trends of U.S. fiscal and monetary policy have been worrisome, they are still better than those seen in any of the main U.S. dollar alternatives. So on a relative basis, the dollar still reigns supreme. Not only does it now reign supreme — we do not see the prospect of its being dethroned by any competitor in the near or mid-term. The grandstanding of Russia and China in this regard is, for now, pure geopolitical bluster.The arrival of government-issued digital currencies may fundamentally shift the landscape — we’ll discuss that prospect below.

The index most commonly used to assess dollar strength relative to other currencies is the DXY. It is an index comprised of six globally traded currencies:

- Euro (EUR) at 57.6%

- Yen (JPY) at 13.6%

- Pound Sterling (GBP) at 11.9%

- Canadian Dollar (CAD) at 9.1%

- Swedish Krona (SEK) at 4.2%

- Swiss Franc (CHF) at 3.6%

The reason that some major currencies are missing — for example, the Chinese yuan or the Indian rupee — is that these currencies do not trade freely on a global market. (Note that this is one reason why, in our view, the yuan will never be a global competitor to the dollar unless there is regime change in China — the current Chinese government would never relinquish control of its currency, and the domestic political power that grants, to international capital flows.)

U.S.-based investors of course have the ability to hold their cash in other currencies, so after the asset allocation question of “how much cash” is answered, the next question is: which cash shall I hold?

For most investors, the answer is clear, as noted above: the U.S. dollar remains the clearest choice.

Source:Marketwatch

The Euro

The euro is a basket case of a currency, for reasons we noted last week. Fundamentally, Europe is a half-finished project, with a unitary monetary policy but a pluralist fiscal policy. That has meant persistent, and occasionally extreme, stresses between the frugal, responsible north and the less frugal, more irresponsible south — which would ordinarily have solved its problems through default, but can no longer do so, and must therefore endure economy-crushing austerity as a result of bloc-wide Eurozone policy. Layer on top of these basic, unresolved problems the current energy crisis brought on by extremist environmental policy conceits and geopolitical hubris, and you have a recipe for a fundamentally weak construct meeting a hard wall of economic and geophysical reality. Layer on top of that an overweening regulatory state that we view as fundamentally hostile to innovation and entrepreneurship. Not good.

The Pound

The British pound finds itself in a similar, though not quite so dire situation. Battered by Brexit uncertainty, and by the same energy constraints now being forced on Europe, it is also under pressure. Out from under the dead hand of the European regulatory super-state, we do see potential good prospects for the U.K., and it is just possible that a change of leadership (both the political leadership and the new monarch) may energize a change of market sentiment on the U.K. if not yet a real change of fortune. That would be a trading opportunity, though — not an invitation to hold large pound deposits or other pound-denominated assets.

The Yen

The yen presents its own set of problems. The Japanese central bank, faced with the alternatives of (1) supporting the yen on global currency markets, or (2) maintaining its policy of “yield curve control,” has opted for the latter. This is a dark cloud with a silver lining. The dark cloud is Japan’s energy dependence — and since global energy is priced in U.S. dollars, a weak yen means higher energy costs (layered on to the rising cost of energy driven by scarcity and geopolitical disruption). The silver lining is that Japan is one of the world’s great exporters, and the rest of the world will now be more able to afford its goods. By all accounts, life on the ground in Japan is quite good for Japanese citizens, in spite of all these gyrations — but they certainly don’t make the yen an appetizing destination for U.S.-dollar denominated investors. Make no mistake, Japan faces acute long-term challenges economically and demographically. The cost of living in Japan is high and growth prospects are dim. When we say life is quite “good” in Japan, in many ways we are referring to the fact that economic dislocations and challenges do not seem to be undermining the social fabric of this stoic, law-abiding society. The chart below of the Yen’s decline is not illustrative of Japanese quality of life.

Canada and Australia

As a resource economy closely linked to energy, timber, and precious metals, Canada is more interesting than many of the other DXY basket components; we believe that in the longer run, a global macro environment favorable to scarce resources and their producers is emerging. However, this is not going to be an “up and to the right” phenomenon. It will be volatile, because sentiment will shift rapidly with economic ebbs and flows — and it is likely that we are setting up currently for a global “ebb” that will see resource prices decline, and the Canadian dollar with them. The same reasoning applies to Australia — though Australia’s proximity to and dependence on China exposes it to more China risk, both economic and geopolitical. Conversely, as mentioned in our global equity market review two weeks ago, Canada’s proximity and dependence on U.S. markets for about 75% of their exports, gives the loonie some relative stability.

Other Alternatives: Gold and Cryptos

While gold is typically considered a commodity (indeed we mentioned it under that rubric last week), one of its perennial roles is that of a currency: an anti-fiat currency whose supply growth is physically constrained. Unfortunately, it is still subject to heavy manipulation by both government and private actors. Interest in gold also seems to have waned in recent decades, especially among younger generations of investors, who see the “here and now” of cryptocurrencies, and may not appreciate the historical utility of gold.

Gold has served well historically to preserve purchasing power when currency machinations have challenged that power, and it is likely to continue to serve that role in the future: a tool to preserve wealth, but not to grow it. It is also possible that much of the public speculative fervor for cryptocurrencies was just a creature of the flush-liquidity “easy money” era that seems for now to be passing into the rear-view. For those reasons, gold remains a respectable (and depending on where you are in the world, maybe even a necessary) allocation or hedge.

Cryptocurrencies are a newer and riskier prospect. Last week we called them a “new asset class,” and so they are — though even more than gold, they present the tantalizing prospect of functioning as currencies that exist outside the fiat system and the control of governments. On balance, we believe this potential usurpation of fiat’s role by cryptos is a utopian dream that is unlikely to come to fruition. Governments will not tolerate the emergence of a genuinely autonomous competitive system that would sharply restrict their ability to influence the economy via monetary policy, or secure tax revenues.

We think the regulation of cryptos is in the early innings, and is only likely to get more restrictive as time goes on. In the last analysis, (1) the government’s ability to levy taxes; (2) to demand that those taxes be paid in fiat; and (3) to choke the conduits running between the crypto ecosystem and the legacy financial system all suggest that “crypto maximalism” is ill-considered.

It is possible to sketch out future scenarios in which technological improvements to cryptos, and profoundly irresponsible government fiscal and monetary policies, create a situation in which more and more of daily life is transacted in crypto outside the government’s purview. But those scenarios, we believe, are highly unlikely, and do not reckon with the ancient and unsleeping determination of government to retain regulatory control of the financial system. Regardless of how skeptical you may be about cryptocurrencies today, recognize that the global forces are aligning to make digital money our future.

The Ethereum “merge” — the network’s transition from proof of work to proof of stake, expected imminently — will showcase, for good or ill, the innovative character of the crypto industry. It may be a positive or a negative catalyst — and the long-term ramifications may take awhile to play out. Many high-profile hacks and accidents have transpired in the crypto ecosystem in recent months. Our popular culture is enamored of all things tech and sometimes seems to assume that experts can’t make damaging mistakes. In our mind it is a very open question how robust proof of stake algorithms will be as bulwarks of genuine decentralization — even if the transition initially seems to go off without a hitch. Crypto speculators should watch carefully.

Government-Issued Digital Currencies

While governments are likely to act decisively to restrict genuinely decentralized cryptocurrencies, most are already developing digital versions of their own fiat currencies — so-called “central bank digital currencies” or CBDCs. The exact shape these digital currencies will take is still unclear; some plans envision them as being assets that individuals can hold, while in other schemes they are tools that foreign and domestic banks and other financial entities will use to transact among themselves. These new digital currencies will bestow on their issuers a host of new potential powers to surveil and sanction individuals, firms, and types of financial behavior, as well as give them “innovative” tools for the conduct of monetary policy.

We think it’s likely that digital currencies will be rolled out to deal with some future crisis when the existing tools prove to be inadequate. The keynote here is “control.” Digital currencies could be targeted at specific groups or geographies; programmed to expire if unused; permitted to be spent only in particular venues or for particular goods and services; or withdrawn from particular sanctioned individuals. Not all of these functionalities will be used at first, but the logic of such digital currencies is unfortunately inexorable. Such events will intensify the efforts of many to maintain a foothold in the non-fiat universe, whether that is gold, decentralized crypto, or other under-the-radar tangible assets, which would increase in attractiveness as this scenario unfolded. The future is likely to be interesting.

The Effects on Other Asset Classes

Of course, relative currency valuations — as we noted above about the yen — have profound influences on global trade and on the demand for assets other than currencies. The perennial strength of the U.S. dollar and the open character of the U.S. financial system have meant that global investors have shown consistent demand for U.S.-dollar denominated financial assets (especially U.S. stocks and bonds) as well as real assets (especially real estate). As long as the U.S. dollar reigns, the global “flight to safety” will be to the U.S. dollar. With the panoply of geopolitical risks now in play, and a nervous global investing public, that long-term trend looks operative in the near term as well.

On the one hand, this challenges the earnings of U.S. multinationals, whose overseas customers will see their purchasing power erode. On the other hand, it strengthens domestically-focused U.S. firms, who enjoy higher purchasing power for foreign-sourced inputs, as well as U.S. consumers. The strengthening dollar takes some of the sting out of global inflation. Tangible goods are increasing in price across the board, but for U.S. consumers buying imported goods, this is somewhat blunted by a strong dollar relative to other global currencies. (Of course there are still present and emerging risks to drive inflation higher from forces beyond central bankers’ control — such as a U.S. rail strike that threatens another round of supply chain and economic disruption. We always monitor these closely.)

Dollar strength is especially relevant for investors interested in foreign stocks. Foreign stocks are of course denominated in the currencies of their home countries (even when those are “translated” into dollar values for U.S.-traded shares). In order for a foreign-currency investment to be worthwhile, the position’s upside must be sufficient even in dollar terms, i.e., even when account is taken of the foreign currency’s risk of devaluation against the dollar. That can be a difficult standard to meet in a period of accelerating dollar strength.

We do see some situations that merit investors’ attention: for example, Brazil, where political risk is again at play (with Lula’s potential return to leadership), but where the underlying strengths of the economy in tangible agriculture, energy, and industrial commodities are well-suited to the emerging global environment of resource scarcity.

Of course, the elephant in the room is the Fed, inflation, and interest rates. Rest assured, we’ll be talking about these a lot in coming weeks.

Thanks for listening, and stay tuned for more thoughts on where we see places to make money.